Ouroboros Design Essay

Featured in PATINAPATINA Magazine

Essay Featured: Carolina Uscátegui

Curators & Creative Directors:

Maham Momin & Dan Cui

The Ouroboros is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon eating its own tail. It’s often seen as a representation of the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth.

“As I am embraced by the sweet Ouroboros, the eternal serpent, I am reminded of nature's cycles. Each being, every creation, dances through the sacred rhythm of birth, life, death, and rebirth. In honouring these truths—embracing their essence and our mortality—we find the alchemy of transformation. With its solemn touch, may death guide us toward a transformative balance within the universe.”

Early alchemical ouroboros illustration with the words ἓν τὸ πᾶν ("The All is One") from the work of Cleopatra the Alchemist in MS Marciana gr. Z. 299. (10th century) Ouroboros. (2025, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

Death has always had a presence in my life. At a young age, I recalled a curiosity for spirits— and harbouring forms of communication that were impossible to see physically but existed in a different realm. Throughout my childhood, I had two near-death experiences that forced me to face my mortality. Into my teens and adulthood, I found profound comfort in the goth and leaned into literature such as Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelley and the illustrative work of H.R. Giger. All brought together the presence of birth and death and its definitive interconnection with nature. It has become a natural transition for me as a graphic designer to explore how death plays a role in design. Especially in an industry that constantly aims for 'timelessness' and 'eternal visuality.' Death—is the constant of life, and when there is no death, there is imbalance.

Due to societal and cultural factors, the perception of death is viewed as taboo or faux pas by Western societies. The discomfort is associated with the unknown aspects of what lies beyond life, and the unwillingness to recognize the inevitability of the unknown furthers that discomfort. Western culture is engulfed by the fantasy of eternal youth, vitality, and productivity. Therefore, in this fantasy, death is the most tremendous inconvenience. However, Western culture is not only afraid of the unknown but also cannot come to terms with the immense emotional labour involved with mourning, and to take it a step further, mourning the existence that was never met. The chosen blindness to death allows a society to function in its dysfunction caused by overconsumption and overproduction. Creating the cultural fallacy that eternity is possible, generating a reality where death is a choice, not an absolute.

Recognizing the tension between the West's interpretation of death and my awareness of it has allowed me to explore how, as a maker, I can use death to return balance and uphold a cycle of transformation. This is broken into a method that aligns with the natural cycles of our Earth, Universe, and Humanity rather than the synthetic cycles practiced in the design industry. I will coin this process of thought and practice as Ouroboros Design. Ouroboros Design begins by acknowledging the presence of death in the natural world, following the development of the visual languages and materiality associated with it, and, lastly, the acceptance of the order and process. In this essay, these three processes will be further explored in my practice; the acknowledgment of death as a natural and constant is presented through the vast research in the subject matter ranging from philosophical to scientific, all resources uniting to support the methodology further. Secondly, visual languages of birth and death are dissected in my Master’s Thesis work (DE)COMPOSITION: The Death of Graphic Design and the Rebirth of a New Practice through material exploration and inter-species collaborations. Finally, the most arduous aspect—acceptance—is addressed in my Bachelor of Design project, The Ritual of Oro. This project profoundly analyzes how visual design can invoke the dead and facilitate its acceptance.

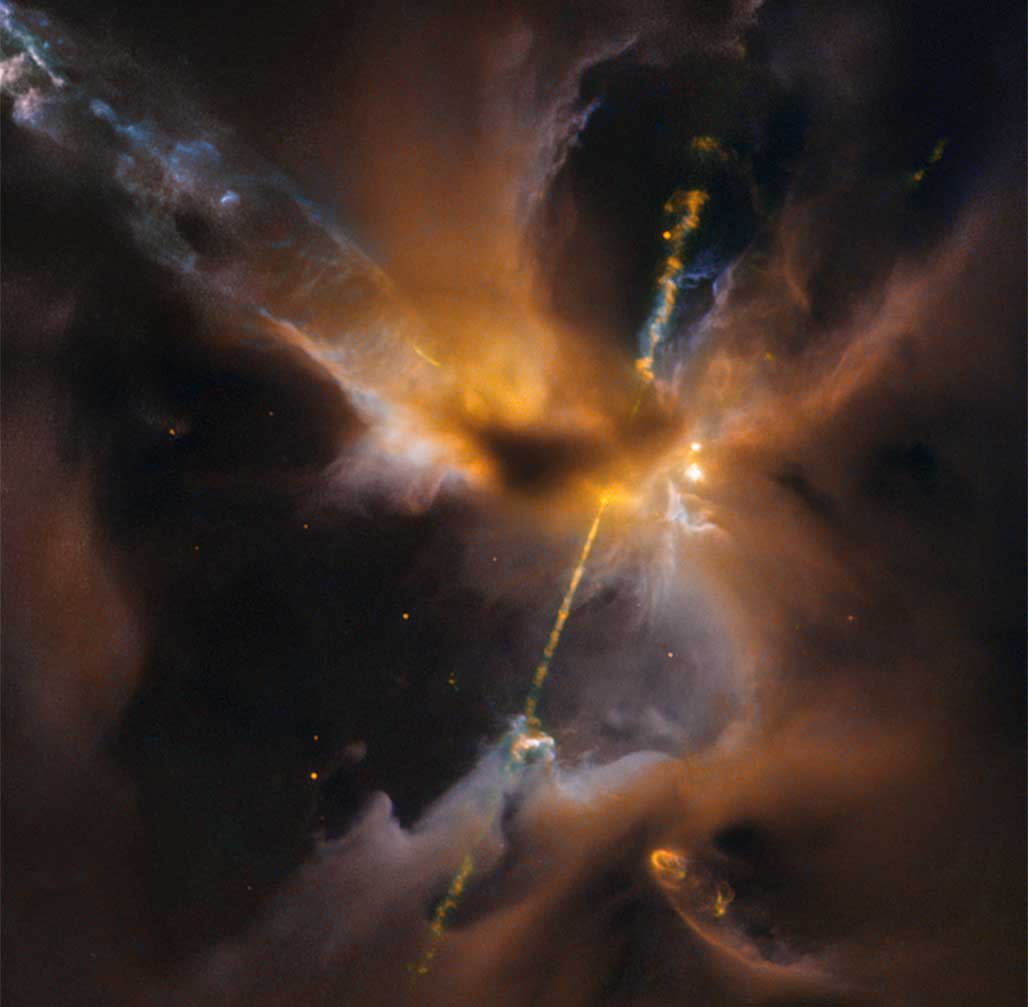

HH 24 : The two lightsabre-like streams crossing the image are jets of energised gas, ejected from the poles of a young star. If the jets collide with the surrounding gas and dust they can clear vast spaces, and create curved shock waves, seen as knotted clumps called Herbig-Haro objects. ESA/Hubble & NASA, D. Padgett (GSFC), T. Megeath (University of Toledo), and B. Reipurth (University of Hawaii)

First, acknowledging death begins with recognizing its presence, from the smallest cell in our body to the vastness of the cosmos. Visualizations such as Powers of Ten by Charles and Ray Eames allow one to recognize our proportion to existence. You Look up to the sky and see tiny speckles of light, distant planets, Mars, Venus, and the moon, but to the blind eye, you also witness and exist during one of the most potent acts of death, rebirth, and transformation. The neutron star is a remnant of a massive star exploding, collapsing into itself and embodying the cosmic drama of death, birth, and transformation and becoming a powerful symbol of the intricate tapestry between life and death in the vastness of the cosmos. Nevertheless, you realize that even in the cosmos, millions of light-years away, these natural cycles of death still occur. They further confirm that birth, life, death, and rebirth are as present in our body's cells as in the universe. They surround me with the internal conflict of why my creation process, as a designer, does not follow this natural order. How do I create with the neutron star? How do I implement a cycle of life, death, and rebirth into my design process? How do I remove myself from a process that inevitably leads to a purgatory of nothingness?

Three books influence this train of thought:

First, Colombian-American anthropologist Arturo Escobar's Designs for the Pluriverse introduces a design practice prioritizing plurality, relationality, and reciprocity. These designs are grounded in indigenous knowledge systems and feminist thought, offering alternatives to the dominant Western development model. I desired to explore a world in which graphic design as we know it dies and new communication systems arise. In this world, communication is between humans and interspecies, from the tallest tree, General Sherman (which I had the honour of visiting in the Fall of 2022), to a one-year-old child. These creatures are so different from each other, but both are deeply connected by existing on this planet and their inevitable role in their existence. This new design practice views designers as creators, collaborators and stewards of the Land. They are responsible for seeing their creations embedded in the cycle of existence in which they are so strongly tied.

The second influence is a Canadian researcher, and designer Max Liborirons's Pollutions is Colonialism, precisely two quotations:"Land with a capital L, which comes out of various Indigenous cosmologies, is not the same as land with a small l used in terms like landscape that are common nouns in English. Land is about relations between the material aspects we might think of as landscapes–water, soil, air, plants, stars— as well as histories, spirits, events, feelings, and other more-than-human relatives."

"They use the Land to extract value, such as in mining, but use the Land as a place to put pollution — from radioactive waste to urban sewage — as another way to make economic value. Using the Land for the best interests of industry, profit, settlers, or colonial governments is a central to colonialism."

Land with a capital L—changed my perception of my surroundings. Where I stand now, my feet on the ground, this Land is home to thousands of bugs, microbes, worms, minerals, water, oxygen, methane, mycelium, roots, seeds, etc. All under my feet, the land is a living system I am part of and an organ of it. When I design, I must design with Land, my collaborator and partner, and a union that listens to and respects it. What I create should not deplete the Land but enrich it by fulfilling its needs.

The third and final influence was Potawatomi Scientist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer's book Braiding Sweet Grass. Kimmerer shares traditional indigenous teachings alongside scientific insights, demonstrating how these two perspectives complement each other. She encourages readers to reconsider their relationship with the Land and recognize the natural world's inherent value and wisdom. It is a celebration of indigenous knowledge, a call to action to protect the environment, and a reminder of the interconnectedness of all life on Earth. Kimmerer's Essay The Honorable Harvest states,

"I am a mere heterotroph, a feeder on the carbon transmuted by others. In order to live, I must consume. That's the way the world works, the exchange of a life for a life, the endless cycling between my body and the body of the world."

Consumption is often criticized, yet it mirrors the natural cycles of life. It is overconsumption that disrupts this balance. In death, our bodies feed the earth: bones provide potassium to roots, flesh nourishes insects, and the Land reclaims us to foster new life. Our existence is a cycle of birth, life, death, decay, and rebirth. Recognizing the purpose of death, we must apply this natural design to our material practices—to regain balance.

Frameworks evolve from a tapestry of influences, inspirations, and lessons learned through rigorous research, application, and relentless iteration. While I've highlighted three key influences in the Ouroboros Design framework, numerous scholars, designers, and innovators have contributed to its development and continue to do so.

The above images is the three poster developed and grown from bacteria, screen printed with decomposing ink, to later decompose into composte.

My Master's Thesis (2023), (DE)COMPOSITION: The Death of Graphic Design and the Rebirth of a New Practice, investigates the visual languages and materiality associated with this cycle of birth, life, death, decay, and transformation. Acknowledging the current limbo of the design industry—trapped in a continuous cycle of creation and overconsumption—it's essential to critically examine the industry's neglect of its role and responsibility in the natural processes of birth, death, and transformation. How do we function outside this purgatory as designers (considering design is a labour and service)? My answer was to kill the practice and propose the death of it; with death comes re-birth and transformation, creating a new practice that aligns with Earth's natural cycles and fulfills the different phases of reciprocity. Referencing not the cyclical purgatory of the current practice but rather the cyclical themes of Ouroboros. Ouroboros, often depicted as a snake eating its tail, has been a symbol of death, rebirth, destruction, and transformation but, most importantly, a unity of all things. By understanding the framework of the methodology, the symbols and the themes, I began to develop a formula and rule that stands for the practice of (DE)COMPOSITION.

The materiality of (DE)COMPOSITION is unique as it follows the framework and commands questions such as, ‘How does a design birth itself?', ' How does it have its autonomy of decision?, and 'How does it die, and the death catalyze a new beginning?'. Using biology, I built a poster that would grow itself through microbial intelligence, allowing the poster to live by providing an environment where slime mould can expand its vessels and feed itself. Lastly, the poster would die, transform, and reciprocate into its environment. Time plays a significant role in the framework; it is often seen as an enemy to most designers—not in this process—time is no longer is my foe but rather my partner. Famous Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote in One Hundred Years of Solitude, “Time was not passing…it was turning into a circle,”. Time provides the wisdom of growth; it’s the material of memories, care, pain, birth, life, and death. I let time grow the bacteria into sheets of flesh, let the slime mould grow vessels to feed itself, and most importantly, the time allowed the worms to consume the material and extract it into valuable rich compost for my herbs.

![]()

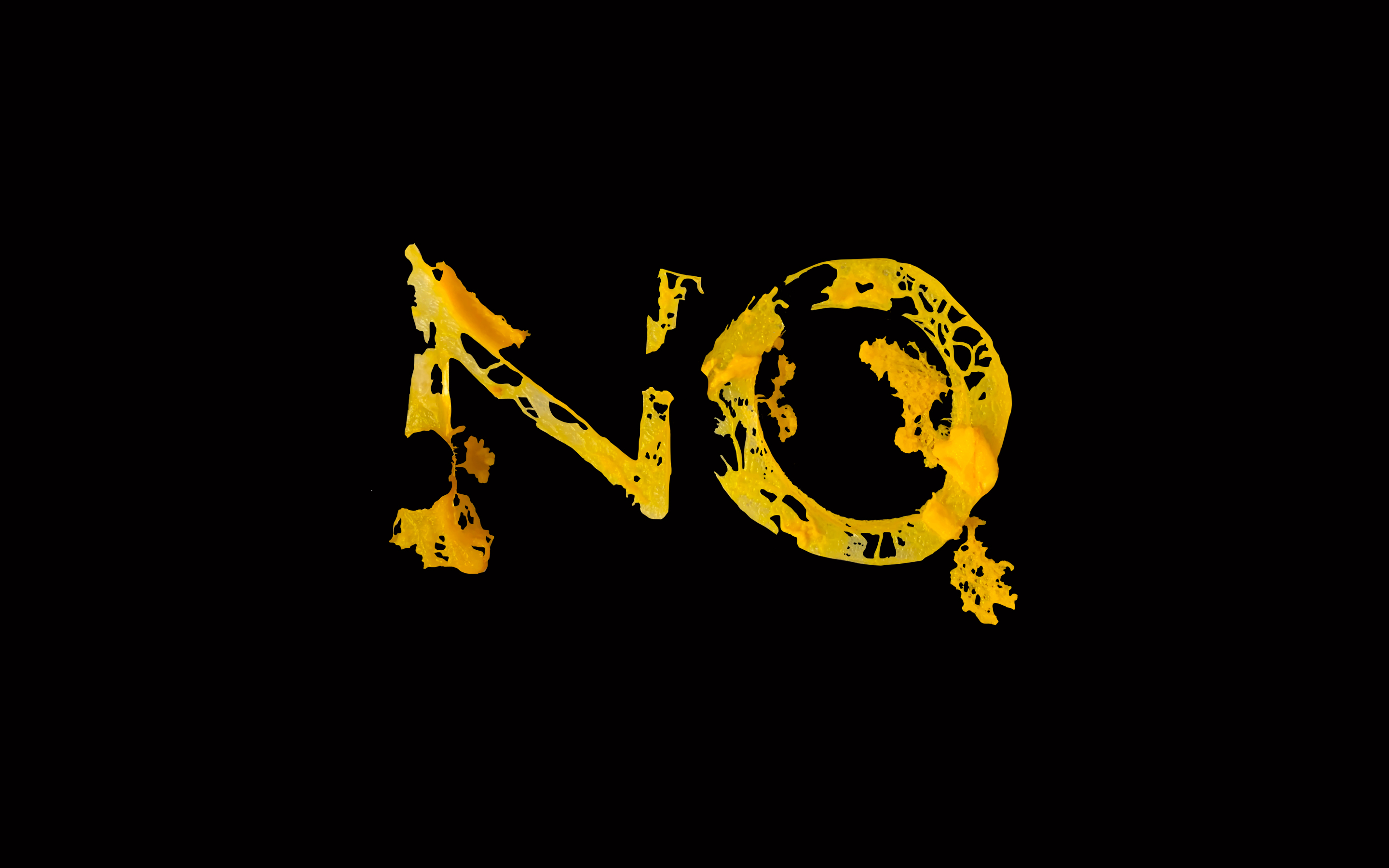

Myxogastria forming the word “NO” . To live is to communicate, whether to other creatures or the body's own internal communication and reception of existing. Collaborating with Myxogastria, a slime mould, it built its own language. Providing a new Roman alphabet that communicates inter-species. The Romans used chisels to carve their alphabets, and I collaborated with slime.

Ultimately, the most critical aspect of Ouroboros is accepting death, even in the most challenging circumstances. In The Ritual of Oro, a project I completed in my Bachelor of Design, I prompted the question, “How do we mourn those we do not know in a space that is complicit for their deaths.” Mourning's impact is rooted in a personal experience—you mourn because what has passed has been so profoundly ingrained in your being. At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned when a society willingly chooses to close its eyes to death and mourning, a state of dysfunction forms. For example, Colombia is known to have the highest homicide rate towards human rights, environmental and Indigenous leaders in the world. As stated in this Guardian Article, Almost half of human rights defenders killed last year were in Colombia, “Colombia was the deadliest country in the world of human rights defenders in 2022, accounting for 186 killings – or 46% - of the global total registered last year.” Yet, upon deeper examination, these killings often stem from insatiable greed, unchecked power dynamics, and the ruthless exploitation of environmental resources like mining and oil. One of the most significant presence in the Colombian mining industry is Toronto’s GCM or Gran Colombia Gold, which has faced several Human Rights violations and lawsuits. Therefore, as a Colombian living in Toronto, Canada, I had to face my connection to the violence inflicted on my country and people.

![]() An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires. Ouroboros. (2025, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires. Ouroboros. (2025, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

Notes:

My Master's Thesis (2023), (DE)COMPOSITION: The Death of Graphic Design and the Rebirth of a New Practice, investigates the visual languages and materiality associated with this cycle of birth, life, death, decay, and transformation. Acknowledging the current limbo of the design industry—trapped in a continuous cycle of creation and overconsumption—it's essential to critically examine the industry's neglect of its role and responsibility in the natural processes of birth, death, and transformation. How do we function outside this purgatory as designers (considering design is a labour and service)? My answer was to kill the practice and propose the death of it; with death comes re-birth and transformation, creating a new practice that aligns with Earth's natural cycles and fulfills the different phases of reciprocity. Referencing not the cyclical purgatory of the current practice but rather the cyclical themes of Ouroboros. Ouroboros, often depicted as a snake eating its tail, has been a symbol of death, rebirth, destruction, and transformation but, most importantly, a unity of all things. By understanding the framework of the methodology, the symbols and the themes, I began to develop a formula and rule that stands for the practice of (DE)COMPOSITION.

α∪Ω

I.

Firstly, one must design with a beginning, an alpha α, the beginning of a transformation.

II.

Secondly, if there is a beginning, an alpha α, there must follow an end, the Ω the omega.

III.

Lastly, it is between the α and Ω that (DE)COMPOSITION occurs. The living matter that you decide to collaborate with—unites with you. The process is never singular but rather a collaboration; it is a union ∪ between one and nature.

Lastly, it is between the α and Ω that (DE)COMPOSITION occurs. The living matter that you decide to collaborate with—unites with you. The process is never singular but rather a collaboration; it is a union ∪ between one and nature.

The materiality of (DE)COMPOSITION is unique as it follows the framework and commands questions such as, ‘How does a design birth itself?', ' How does it have its autonomy of decision?, and 'How does it die, and the death catalyze a new beginning?'. Using biology, I built a poster that would grow itself through microbial intelligence, allowing the poster to live by providing an environment where slime mould can expand its vessels and feed itself. Lastly, the poster would die, transform, and reciprocate into its environment. Time plays a significant role in the framework; it is often seen as an enemy to most designers—not in this process—time is no longer is my foe but rather my partner. Famous Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote in One Hundred Years of Solitude, “Time was not passing…it was turning into a circle,”. Time provides the wisdom of growth; it’s the material of memories, care, pain, birth, life, and death. I let time grow the bacteria into sheets of flesh, let the slime mould grow vessels to feed itself, and most importantly, the time allowed the worms to consume the material and extract it into valuable rich compost for my herbs.

With time comes care. Care was a significant aspect of collaboration with these microbes and moulds. Temperature, feed, and acidity are all cared for daily. Interestingly, as I tended to these creatures during this time, I tended to myself as I healed from three life-threatening health conditions; I felt I cared for them. They cared for me. Perhaps that's the beauty of Ouroboros—I knew that in the months coming, these creatures would pass and transform into a new material that would feed back into nature. I was a mere steward in their life, feeding them and caring for them for their new purpose, as I too am this creature and tend to the care of my community, family, and environment to then support me in my final days in this cycle—and aid in my transformation of whatever my new purpose would be. I am the worm, and the worm is me; I am the slime mould, and the slime mould is me. I am that bacteria, and that bacteria is most definitely me. With the care came communication—I built a language with them; the Latin letters from the slime mould grew into changed forms. The Romans used chisels to create their alphabet; I collaborated with slime to build ours. Over time, my collaborators and I developed a unique interspecies language, enabling us to communicate seamlessly with one another. (DE)COMPOSTION is my life's work; it explores the possibilities of designing with death's materiality to further the world's balance—designers not only as makers but also as stewards.

Myxogastria forming the word “NO” . To live is to communicate, whether to other creatures or the body's own internal communication and reception of existing. Collaborating with Myxogastria, a slime mould, it built its own language. Providing a new Roman alphabet that communicates inter-species. The Romans used chisels to carve their alphabets, and I collaborated with slime.

Ultimately, the most critical aspect of Ouroboros is accepting death, even in the most challenging circumstances. In The Ritual of Oro, a project I completed in my Bachelor of Design, I prompted the question, “How do we mourn those we do not know in a space that is complicit for their deaths.” Mourning's impact is rooted in a personal experience—you mourn because what has passed has been so profoundly ingrained in your being. At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned when a society willingly chooses to close its eyes to death and mourning, a state of dysfunction forms. For example, Colombia is known to have the highest homicide rate towards human rights, environmental and Indigenous leaders in the world. As stated in this Guardian Article, Almost half of human rights defenders killed last year were in Colombia, “Colombia was the deadliest country in the world of human rights defenders in 2022, accounting for 186 killings – or 46% - of the global total registered last year.” Yet, upon deeper examination, these killings often stem from insatiable greed, unchecked power dynamics, and the ruthless exploitation of environmental resources like mining and oil. One of the most significant presence in the Colombian mining industry is Toronto’s GCM or Gran Colombia Gold, which has faced several Human Rights violations and lawsuits. Therefore, as a Colombian living in Toronto, Canada, I had to face my connection to the violence inflicted on my country and people.

By crafting a mourning ritual in five solemn steps for all souls killed. Igniting the ritual with a book that, through the warmth of the living, reveals the names of the murdered, beading money to honour each life, and concluding with a wail, each step symbolizes a profound acknowledgment of the ceaseless toll of death and humanization of each person. He was a father, she was a mother, he was a brother, she was a sister—they were all people with dreams and fears. My role as a designer was to be a conduit to communicate the dead, as death has over-consumed Colombia. The work of The Ritual of Oro haunts me to this day. Still, it was a necessary piece in evoking methods of communication with the dead, especially in times like today (2024). This piece is a reminder of the need to humanize the dead in times when the world will not acknowledge their humanity, or else we will lose our humanity.

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires. Ouroboros. (2025, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires. Ouroboros. (2025, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OuroborosTo conclude, as I am embraced by the sweet Ouroboros, the eternal serpent, I am reminded of nature's cycles. Each being, every creation, dances through the sacred rhythm of birth, life, death, and rebirth. In honouring these truths—embracing their essence and our mortality—we find the alchemy of transformation. With its solemn touch, may death guide us toward a transformative balance within the universe.

Notes:

- Powers of ten, 1978. Santa Monica, CA: Pyramid Films, 1978.

- "Neutron Stars." Imagine the Universe! NASA, March 1, 2017. https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/science/objects/neutron_stars1.html#:~:text=Neutron%20stars%20are%20formed%20when,and%20electron%20into%20a%20neutron.

- Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

- Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

- Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Ouroboros." Encyclopedia Britannica, June 19, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ouroboros.

- Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, trans. Gregory Rabassa (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), Chapter 7.

- When referring to collaborators I am referencing the bacteria, slime mould and worms that supported in the process of (DE)COMPOSITION.

- "The Guardian," last modified April 4, 2023, accessed June 23, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/04/colombia-human-rights-defenders-killings-2022.

- Sydow, Johanna. Gold mining, human rights and due diligence in Colombia, November 19, 2019. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Gold%20Mining%2C%20Human%20Rights%20and%20Due%20Diligence%20in%20Colombia.pdf.